Navajo Joe (1966) and The Mercenary (1968) are each Italian Westerns directed by Sergio Corbucci and scored by Ennio Morricone.

Sergio Corbucci is often referred to as “the other Sergio” when movie folk discuss Italian Westerns. He is certainly less famous and commercially, his movies can’t rival Sergio Leone in terms of revenue and prestige.

However, while Leone makes epics – Corbucci makes unique, stylized, enjoyable Westerns – several of which are likely unappreciated. While Django and The Great Silence have recently earned a reputation for their gritty, dark quality, Navajo Joe and The Mercenary are two of his best – or at least, most entertaining movies.

Besides Corbucci’s direction, the common link between the two movies are the outstanding scores created by Ennio Morricone.

If you enjoyed Kill Bill, Volume 2, you’re in for a treat.

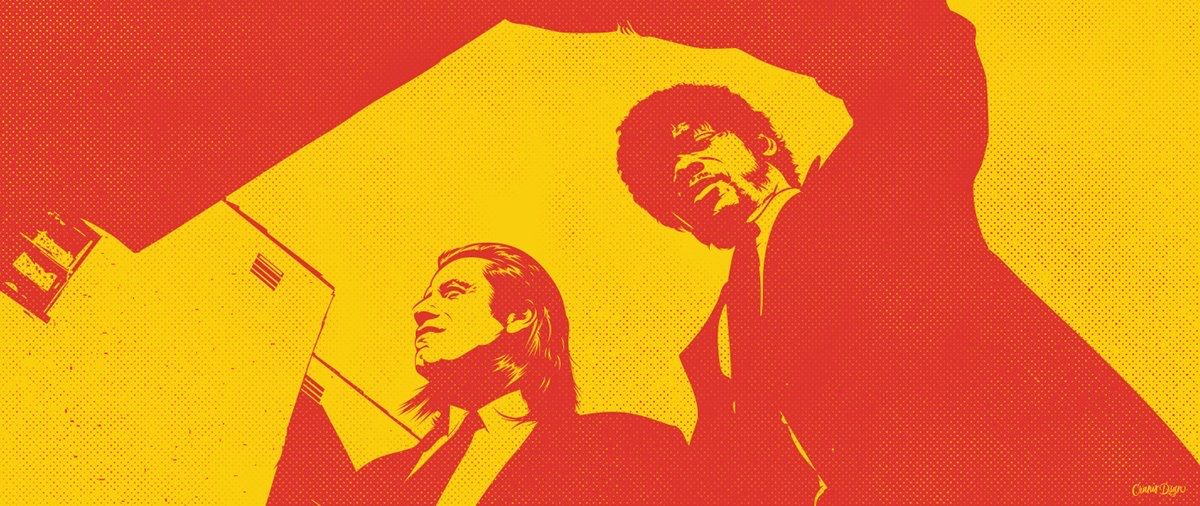

The Mercenary tells the story of Sergei “Polack” Kowalski, a hired gun whose robberies lead to a revolution against Mexican authorities. Kowalski makes a series of deals with Paco, a silver mine worker, and the pair steal money and weapons from the Mexican Army. Throughout their adventures, they are tracked by Curly, an American mercenary. In the process, Paco becomes a famed revolutionary.

Continue reading “Navajo Joe and The Mercenary”