Breathless is Jean-Luc Godard’s first feature movie. Un Flic is Jean-Pierre Melville’s final movie. Both directors are considered essential figures in French New Wave Cinema.

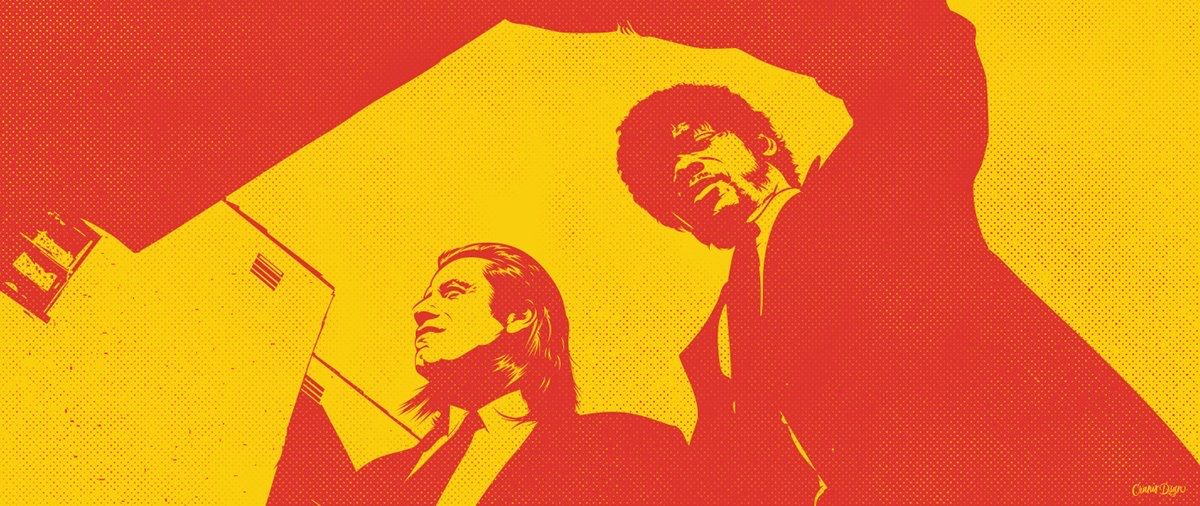

Breathless is to 1960’s French culture what Pulp Fiction was to its 1990’s American counterpart – a purely original work that both reinterpreted and reinvented movies. Each work represents a complete shift in how people made, watched and thought about movies. Both Godard and Tarantino present stories about crimes and gangsters, but each movie lifts the cultural subtext around them into its own powerful narrative form. There is a linear jump from Jean-Paul Belmondo’s Michel imitating a gangster to Samuel Jackson and John Travolta discussing foot rubs.

While there were occasional surprises in the years before Breathless and Pulp Fiction, nothing represented the jolt of energy these movies produced. Even 60 and 30 years later respectively, the two works remain relevant, instantly re-watchable and endlessly copied.

Breathless tells the story of Michel, a small-time crook who impulsively kills a French policeman. He is pursued by French authorities – along the way, he tries to convince American student Patricia to run away with him to Italy. The plot is nearly superfluous, as Godard focuses on the existential roles his lead characters assume. Patricia is sent to Paris by her parents to attend the Sorbonne – she wants to be independent, Michel is a wanted criminal – he wants to be Humphrey Bogart.

At its core, Breathless is a story about youth. Michel and Patricia are vibrant and driven by pure energy: Patricia’s thoughts form a lyric stream of consciousness, Michel is always moving and laser focused on his goals – getting his money and trying to sleep with Patricia. Each is focused on the moment in front of them and the electric vibe of Paris seems to reflect this.

There is a disturbing quality in Godard’s work that perhaps helps to explain why the young are drawn to his films and identify with them, and why so many older people call him a “coterie” artist and don’t think his films are important. His characters don’t seem to have any future. They are most alive (and most appealing) just because they don’t conceive of the day after tomorrow; they have no careers, no plans, only fantasies of the roles they could play, of careers, thefts, romance, politics, adventure, pleasure, a life like in the movies.

Godard’s guerrilla, shotgun filming approach perfectly captures this sentiment. There are no closed sets or permission granted to film – the Champs d’ Elysee buzzes in the background as Michel and Patricia navigate the city. Paris itself is a character in the story – albeit an unsuspecting one on the verge of cultural upheaval – which gives Breathless an eternal feeling of youth and discovery.

Un Flic is director Jean-Pierre Melville’s final movie. It tells the story of Edouard Coleman, a detective tracking a group of thieves. The movie starts with a bank robbery, which in turn finances an elaborate theft of drugs onboard a train. Along the way, a love triangle forms between Coleman and Simon, the mastermind of the scheme and Cathy, his romantic interest.

Melville delivers a precise and calculating heist movie in Un Flic. Nearly every scene is presented in a cool, blue tinge – the characters are efficient: Simon’s group are professional thieves, their manner and dress sophisticated, while Coleman is suave and savagely cunning. Melville’s narrative locks into the actions each character takes to achieves their goals – there’s little subtext to examine or winding conversations to be had. Melville is giving us a serious movie.

The Silences of Jean-Pierre Melville

The main character of Godard’s Bande à part mimics a Hollywood shoot-out, staggering, falling, and rolling about in the manner of James Cagney in Public Enemy; but then at the end when he is actually shot, he goes through the same parodic gyrations long after these real bullets would have silenced him. Godard says that a character is unable to act outside the culture of film, but in fact the character is lost to the foregrounding, the sheer presence, of actor, director, and film. Godard undercuts the authenticity of the scene, which he reduces to a simula-crum of pop cultural images. There is a scene in Truffaut’s Tirer sur le pianistein which a thug says that if he is lying may his old mother fall dead—and suddenly intercut is a scene, in the style of silent films, of an old lady grasping her breast and falling over (Truffaut’s homage to the Hollywood filmRoxy Hart): a break in the level of reality Melville would never countenance.

The pairing of these directors is intriguing. Melville is considered the precursor to the French New Wave that is typically represented by Godard. Melville is even honored to a point in Breathless – he plays a satirical version of himself. Yet Godard is an explosion of youth, energy and an expression of requisite cinematic anarchism. Melville is cool, steely and measured – he’s the fully formed adult master of his craft.

Despite its title, Breathless is a celebration of air and ideas. Everything flows, often in multiple directions. Michel and Patricia’s existential discussions are a sort of lyric prose – it doesn’t follow in a linear pattern or find a resolution – it just breathes. Even Michel’s eventual death and final words are more playful gag than denouement.

In contrast, Melville’s Un Flic is a terse, literal telling of two robberies – one good, the other bad. We don’t learn much about the robbers beyond their basic motivations. While expertly acted, even Edouard is a mystery. We see bursts of anger, but his life as a detective is mechanized craft – his days run together and he ends every phone call with the same phrase. The world he inhabits is full of tight spaces: tiny nightclubs, bare offices, cramped cars. There’s not much room to explore.

While Breathless is young and passionately aimless, Un Flic realizes its place in life. Perhaps the French New Wave has grown up. Melville’s final movie is an accomplishment – it’s a smart, detailed heist movie, something that definitely shouldn’t be taken for granted.

The BEST – The Great Train Robbery

The middle part of Un Flic features a twenty-minute scene where Simon lands on top of a moving train, changes into formal sleep ware and swaps out his luggage for a haul of heroin. It’s a tactically brilliant scene featuring the kind of detail rarely seen in movies anymore.

The BEST – Part 2 -Michel and Patricia in the Hotel

Godard’s jump cuts accentuate Patricia’s fluttering thoughts – she dreams, laments and plans, all while Michel is focused on his immediate needs of money and sex.

The WORST – Cathy’s Lack of Motivation

Cathy is the love interest of both Simon and Edward and while each man seems aware, neither is expressive in their disapproval. Similarly, she isn’t much of a factor in the heist unraveling – despite her proximity to both detective and thief. Perhaps I need a second viewing to explore this character.

FOX FORCE FIVE RATING – Breathless 4.75/5, Un Flic 4/5

Un Flic is a rock solid heist movie and represents the kind of adult work that we rarely see anymore. It’s worth several views and easily should be an inspiration for emerging writer/directors. Breathless simply changed movies. It’s a 60-year old movie that is somehow both fresh and timeless.