A Woman is a Woman is a 1961 movie directed by Jean-Luc Godard.

WHAT HAPPENS?

A young woman wants to have a baby with her boyfriend, whose interests lie elsewhere. His friend is brought into the relationship, which only leads to complicated feelings.

ONE LINE REVIEW

A Woman is a Woman sees Godard take on the absurdity of relationships.

THE ACTORS

Anna Karina stars in her first Godard feature and it’s obvious the director is infatuated with her. Karina’s big, expressive eyes and range of emotion are continually highlighted throughout. Her character, Angela, possesses little depth beyond her main motivation, yet Godard accentuates her naivety and allows her style to emerge.

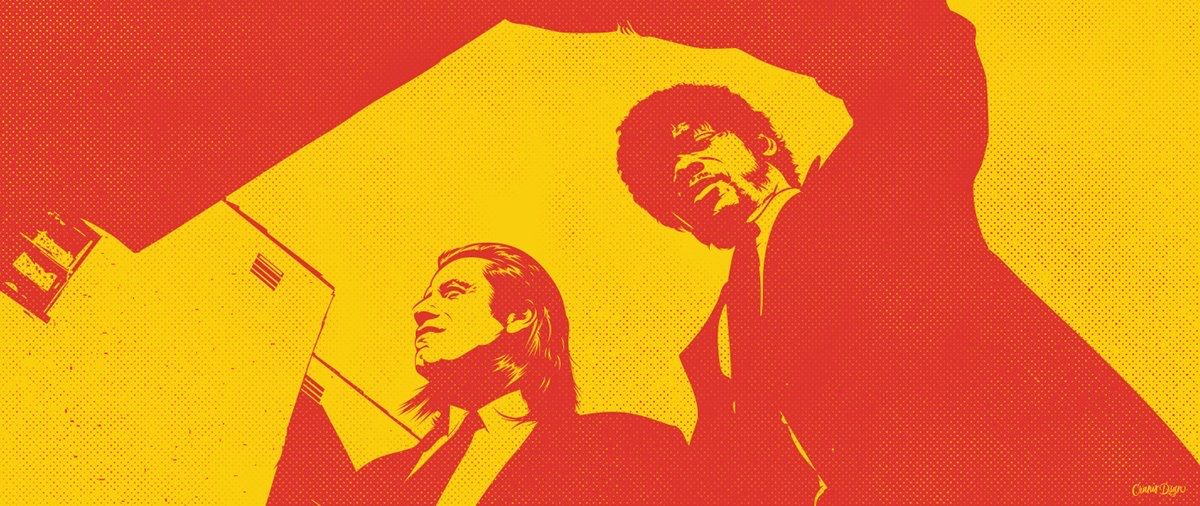

Jean-Claude Brialy and Jean-Paul Belmondo play Emile and Alfred, Angela’s potential suitors. The prolific Brialy is efficient as the cynical and often cold Emile – he continually shoots down Angela’s desire for a baby. Belmondo breezes through his performance as the cavalier Alfred.

THE DIRECTOR

A Woman is a Woman fits into a unique place in Godard’s filmography. There are few gangster references and no overt political leanings present. As such, it features a light tone. Being only his second feature, we also see the subversive experimentation that would mark his later work. Early on, Karina announces: “before acting out our little farce, let’s bow to the audience.”

Throughout the movie, Godard reminds us that we’re watching a movie. Karina makes a regular habit of winking to the camera. Meta moments abound, including Alfred mentioning that “Breathless is on TV tonight.” A police duo interrupt an argument to canvass the apartment. Emile and Angela decide not to talk to each other – instead they argue through book titles.

Continue reading “A Woman is a Woman”