Aguirre, the Wrath of God is a 1972 movie directed by Werner Herzog and starring Klaus Kinski.

Aguirre, the Wrath of God tells the story of Spanish conquistadores searching for the mythical El Dorado in Peru. Crossing the Amazon, the expedition struggles to survive against brutal conditions and hostile natives. Klaus Kinski plays Don Lope de Aguirre, who seizes control of the expedition and leads the group into chaos.

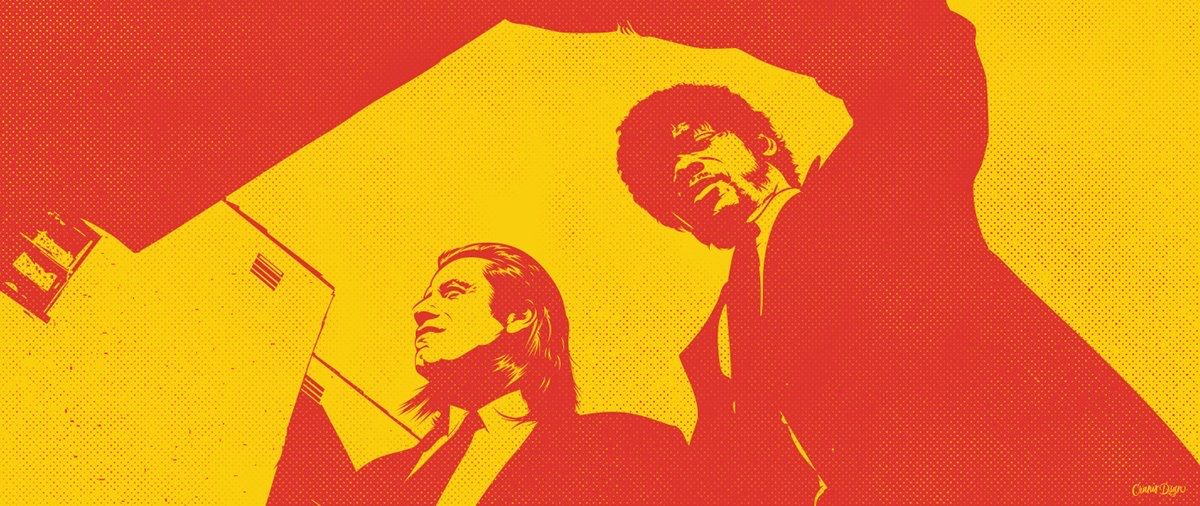

There’s a great chance Kinski is completely miscast as a 16th century Spanish conquistador. He’s slight, wobbly kneed and his kettle helmet barely conceals cascading dirty blonde hair. He’s an art school German out of place in the jungle playing a Spaniard.

Yet, in a Werner Herzog production – one that cannot help blurring the line between fiction and documentary – Kinski is the perfect choice to play Aguirre, a man bent on capturing the illusion of greatness regardless of the human cost.

Further, it takes a performance as outlandish as Kinski gives to honor the spectacle of Herzog’s vision.

The opening scene is majestic. Drifting clouds settle to reveal the enormity of the Andes Mountains before tiny specks come into surface. Herzog’s troupe are trekking down a dangerous slope into the Amazon jungle, hauling along a horse, pigs, chickens, and a cannon. Struggle marks the actors’ eyes as they have become fully immersed outsiders – even the natives are hesitant to find their footing in the treacherous terrain.

Herzog’s crew are essentially conquistadors. We have scripted dialogue to remind us otherwise, but the first portion of the movie feels more like a documentary. A basket of chickens tumbles from a cliff, a rider almost gets hung up on a crooked branch, actors swat away bugs. It’s a dangerous and brutally unfair journey.

The plot develops around the expedition’s leader Pizarro deciding to divide the group and find resources before going further into the unknown. He leaves the nobleman Ursua as his second in command. One of the rafts gets stuck in the eddy and the men are ambushed. Suddenly, the ranks are thin and plotting begins. It doesn’t take long for Aguirre to overthrow the rule of Ursua.

As Aguirre becomes the defacto fictional leader of the expedition, Kinski begins to personify the character. He’s going to battle with his cast mates. As the natives struggle to steady the sedan carrying Ursua’s mistress and Aguirre’s daughter, Kinski manhandles them, grabbing and prodding – berating them for their stumbles. Moments before Ursua is overthrown, Aguirre winds among the soldiers, clutching and pulling them into him – urging them to join his treason.

Beyond the physical, Kinski’s eyes write scenes themselves. Before speaking to Pizarro regarding the group’s strategy, Aguirre dissects his leader with a penetrating glare. Onboard the raft, Aguirre’s gaze is carefully measured on the silent jungle, yet somehow always fixed on a higher mythical plane. The character assumes his destiny is El Dorado – the actor is similarly focused, although it’s hard to detect what drives the mercurial Kinski.

Everything else is a mere obstacle. Aguirre refuses to acknowledge the sickness and agony engulfing his men – instead he proclaims himself as the wrath of God and envisions gaining enough fame and power to overthrow the Spanish crown. Kinski berates his fellow actors and physically attacks them during the cannibal scene where they discover pigs and bananas. He screams at a spooked horse to move out of his way. Kinski is connecting with his character’s madness but his spastic anger also reveals how miscast he is on an arduous movie shoot in the Amazon.

The descents of both actor and character continue as the movie progresses. Aguirre’s crew has been decimated and the stunning finale sees Kinski marching around the dying raft, interacting only with chirping monkeys. The grandiose, unfulfilled narrative continues to escalate – now Aguirre will build a dynasty with his daughter, who is dead from fever. Kinski cradles a monkey, staring into its eyes as if it were a loyal legion of followers.

Herzog is the expedition’s true leader. Aguirre is the director’s first feature movie and he creates – or at least presides over – a remarkable display of realism. The actors are literally stuck in the mud trying to move supplies. There are awkward pauses when the hired native extras try to dart their eyes away from the camera. Smoke billows into scenes, water splashes the lens and the expedition’s horse collapses onto its side.

This realism extends to his direction of the mercurial Kinski. Two fascinating documentaries are companions to Aguirre, the Wrath of God. The first, My Best Fiend, details Herzog and Kinski’s tumultuous personal and professional relationship. The second, Burden of Dreams, profiles Herzog’s agonizing experience making his epic Fitzcarraldo. At times, it’s hard to paint either man as a sympathetic figure – during the making of Fitzcarraldo, Herzog channels some of Aguire’s spirit. Both documentaries illustrate the unique level of genius, fragility and madness in each.

Herzog reveals that he often provoked Kinski into emotional tirades before shooting scenes in an attempt to exhaust his rage. Nearly every collaboration between the two features a story of Kinski attacking Herzog or threatening to walk off the set. Further exploration finds Kinski lashing out at Herzog when the star was not the center of the production’s orbit. It’s an unusually symbiotic and unhealthy relationship.

Burden of Dreams shows the dictatorial side of Herzog. In making Fitzcarraldo, the director is accused of putting his crew in danger in an attempt to pull a massive ship over a mountain into a river. Herzog cites that he was willing to take the same risk as his crew – something also noted in Aguirre, the Wrath of God. The environment Herzog creates – or enables – leads to Kinski’s aggressive outbursts. During the banana scene, Kinski narrowly misses hitting another actor with a full extension of his sword.

Given this context, it’s not surprising that Aguirre, the Wrath of God led to an infamous movie legend. Supposedly, Kinski wanted to leave the remote shooting site before filming was complete. Knowing the catastrophe that would follow, Herzog pulled a gun on his lead actor and threatened him into staying.

It’s hard to know what actually transpired – especially now that only Herzog remains to tell the story. The mystery is fitting, at least as the movie develops. The expedition is slowly dying – the crew is starving and going mad from fever. Aguirre essentially separates himself from the despair, as his vision of dynastic power only grows.

There is a tremendous scene where the remaining crew think they see a boat stuck high in a tree. Okello, the noble’s servant, is hazily processing his thoughts as a native arrow strikes him in the leg. “That is no ship, that is no forest, that is no arrow. We just imagine the arrows because we fear them.” Aguirre senses the phantom ship’s purpose: he will sail to the Atlantic in it.

The BEST – Let it Breathe

The setting is about as authentic as you’ll find in a movie – it’s obvious the crew is struggling in the jungle. Kinski is tempestuous and occasionally dangerous – and your eyes cannot leave him. In the hands of another director, these qualities could easily be exploited. However, Herzog shows incredible restraint in crafting the tense raft scenes. Silence is ominous and usually followed by a volley of native arrows. Even the arrows feature a reserved impact – there are no staggering, dramatic deaths to be found.

The BEST Part 2 – The Wrath of God Speech

The BEST Part 3 – “My men measure riches in gold. I despise them for it.”

This is officially when Aguirre departs from reality. Some part of his delirious mind understands that there is no gold to be found on the expedition. Yet, his quest for power and fame is undeterred.

The BEST Part 4 – Inez Exits to the Jungle

Inez is the mistress of Ursua and probably the expedition’s most logical voice. She immediately senses Aguirre’s craving for power and then later recognizes his descent into madness. Once Ursua is found guilty in a sham trial and his lone protector, the oafish glutton Guzman is killed, she realizes her fate. In a beautiful scene, the soldiers alternate fighting natives and scrounging for food, while she quietly advances into the dark unknown of the jungle.

The BEST Part 5 – The One-Liners

For a movie as gripping, tense and occasionally bizarre as Aguirre, the Wrath of God is, there are some classic lines to be found:

- Guzman is claiming all land he sees: “Have you seen any solid ground that would support your weight?”

- Aguirre on a potential traitor: “That man is a head taller than me. That may change.”

- Carvajal the Priest gets called out: “Monk, do not forget to pray. Lest God’s end be uncomely.”

- The random young soldier who gets speared: “The long arrows are becoming fashionable.”

The BEST Part 6 – Musical Interludes

Perhaps the movie’s most likable character is the unnamed native who plays a piped flute instrument. He shares a scene with Kinski, who is either agitated or frightened by the native’s placid demeanor. For a contrast, Aguirre’s henchman Perucho prefaces his murderous intentions with a low, rhythmic humming.

The WORST – No Animals Were Harmed in the Filming of This Movie…..

About that….

FOX FORCE FIVE RATING – 4.75/5

Aguirre, the Wrath of God is probably not cinematic enough to be considered an epic. Similarly, there’s no tangible lesson or reward awaiting the viewer. It’s a movie that illustrates the punishing effects of nature and the maddening chaos of power. However, the scale of difficulty and lengths Herzog and Kinski reached to create such an environment makes the movie a masterpiece in its own mythical right.