Django Kill, If You Live, Shoot! is a 1967 Italian Western directed by Guilio Questi.

Tomas Milian’s Django is betrayed by his gang following a robbery and left for dead. He recovers and becomes entangled in a bloody battle for gold between corrupt townspeople and a homosexual gang. The movie is wildly unique for its genre, as it presents a surreal Old West landscape that is layered in contemporary references.

Django Kill features a conventional Western story: a mysterious stranger comes to town and finds himself in the middle of a battle between locals and outside forces. Gold and greed are at the heart of the issue and the hero encounters an emotionally wounded love interest.

The presentation beyond the story is what makes Django Kill a fascinating movie.

The lead character, Django, is cast throughout the movie in soft light – almost in a nod to his feminine facial features. His outfit of an unbuttoned leather vest, oversized medallion and headband is decidedly atypical for Western leading men. Similarly, his actions stray from the rugged determinism that defines the genre. He’s bold and physical, yet oddly passive – as highlighted during his capture by “the Muchachos”, an outlaw gang of homosexual cowboys.

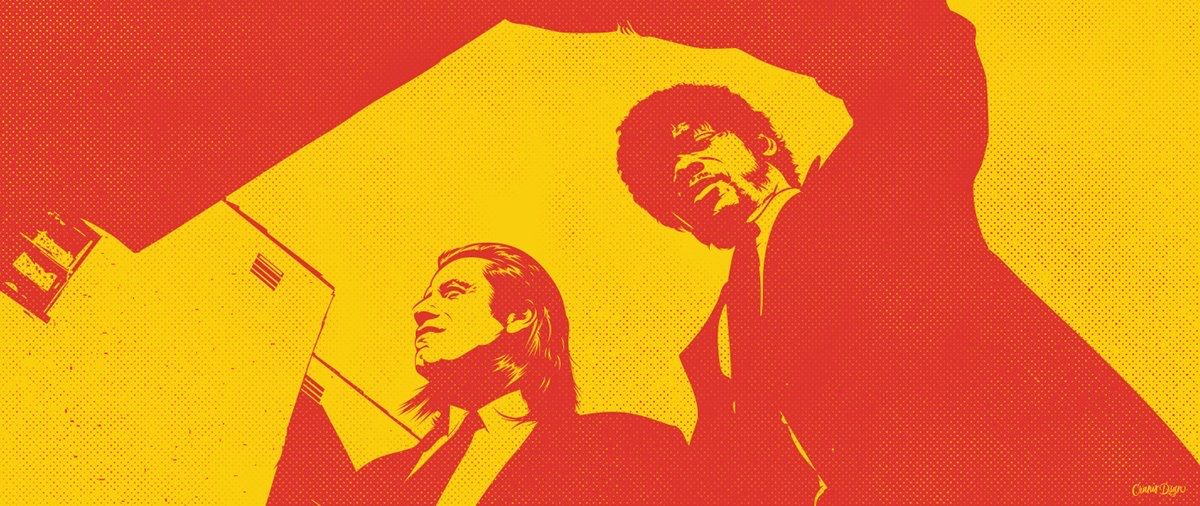

This scene – and image – captures the profound statements Questi is making about the myth of masculinity and authority throughout the movie. He’s challenging these ideas by framing them against Christian ideals.

From the essay, “Homosexuality and the Italian Spaghetti Western”:

Questi’s decision to represent the hero’s enemies as homosexual was definitely a conscious one due to his past as an anti-fascist partisan fighter. Questi’s clan of black-leather clad muchachos references the Italian fascist military groups known as the Blackshirts. Organized by Mussolini and known for their extreme use of violence and recognizable black uniforms, the Blackshirts were imitated by Hitler when he created the Brownshirts. Also known as the SA or Nazi Stormtroopers the Brownshirts have long been associated with homosexuality due to the more or less open homosexuality of its chief of staff Ernst Rohm. The correlation between these two groups and Questi’s Blackshirt muchachos could not be more obvious.

The leader of the Muchachos, Mr. Zorro, continually recruits Django to join his forces. This is typical of Western and Japanese storytelling – as the lone gunslinger or Samurai warrior is often sought after to help steal gold or defend the helpless. However, the benefits awaiting Django are of a physical kind – a feast of food and an orgy with the Muchachos.

Here, the character of Evan serves as a sort of sacrifice. Evan is the son of the corrupt town innkeeper and appears a wayward and disturbed youth. He wants out of his small town and pegs the mysterious stranger Django as his means of escape. Evan is taken by the Muchachos and held hostage while Django is forced to drink. In a bizarre visceral scene, the Muchachos feast on roasted pig and bananas – each bite detailed in vivid descriptions by a series of Questi close-up shots of mouths chewing.

The sequence is a graphic allegory for what occurs off-screen: Evan is raped by the Muchachos. Django, who previously vowed to help Evan, does not intervene. Evan arises the following morning, appearing almost as a ghost, wandering among the carnal wreckage of the previous night. He finds a gun and kills himself.

Evan’s death is a layered event. It’s tragic independent of the story but represents the moral ambiguity of the movie’s lead character. The remainder of Django’s actions appear aimless after witnessing his inaction here. Perhaps Questi is illustrating the futility of the classic Western hero – Django is no longer an atypical hero as he refuses to defend the helpless. Or, Questi may again be pointing to the connection between fascism and homosexuality.

Like most genre conventions in the film he radically changes the homoerotic to something strange and grotesque, mainly homosexuality because of their connection to fascism. In this way Questi’s portrait of the homosexual is a homophobic one and one representative of the Christian condemnation of homosexuality in Italy.

In this sense, Django’s inaction is grotesquely justified, while Evan’s death is necessary to Questi’s argument. The ending of the movie sees Mr. Zorro and his Muchachos ultimately defeated by Django – it’s as if the fascism of World War II has again been destroyed.

The BEST – Django Kill is a Bizarre Biker Movie Trip Masquerading as Western.

From the opening scene, which features an acid trip flashback, to Django’s revival at the hands of effeminate shamans and onwards to a town where women are locked away and children literally kept under the feet of their parents, Django Kill is exceptional in its weirdness and completely original in style.

The BEST Part 2 – Something’s Not Right Here

Questi spins the cliche Western “gunslingers entering a town” into a bizarre carnival of weirdness.

The WORST –Django Kill’s Attempt at Creating a Love Interest

In a movie where the lead actor is stripped to a loin cloth and splayed on a board ala Jesus of Nazareth while tortured by a fascist, homosexual outlaw gang, Django eventually falls for Elizabeth – a woman who has been deemed crazy and locked up by her crooked Alderman husband. It’s only fitting that she sets fire to her house after she and Django share a rather unconvincing night of passion together.

FOX FORCE FIVE RATING – Django Kill 3.5/5

Django Kill is a weird spectacle that has to be seen to be appreciated. The movie is a brilliant experiment in reimagining a genre. Not everything works but that’s part of the beauty of movie making.